Roadmap for Green Finance with Carbon Neutrality Vision (Abbreviated Edition)

Ma Jun, the director of GFC and IFS, leads the research work. The experts in the working group are listed by surname as follows in alphabetical order of surnames:

1. An Guojun (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, CASS)

2. Bie Zhi (Industrial Bank)

3. Chen Hao (Guangzhou Emissions Exchange, CEEX)

4. Chen Liping (CEEX)

5. Chen Yaqin (Industrial Bank)

6. Chen Yunhan (Beijing Institute of Green Finance and Sustainable Development, IFS)

7. Cheng Lin (IFS)

8. Geng Yichen (Ping An Insurance)

9. Han Mengbin (National Institution for Finance and Development, NIFD)

10. He Xiaobei (Peking University)

11. Hu Min (IFS)

12. Huang Xiaoyi (Hwabao WP Fund Management)

13. Ge Xing'an (SusallWave)

14. Jiang Nan (Beijing Green Finance Association)

15. Kang Jinlong (Tsinghua University)

16. Li Jing (Tsinghua University)

17. Li Bingting (Ping An Securities)

18. Li Jian (Agricultural Development Bank of China)

19. Liu Jingyun (Lianhe Equator Environmental Impact Assessment)

20. Liu Kang (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, ICBC)

21. Liu Wei (IFS)

22. Lu Yi (Hwabao WP Fund)

23. Ma Xianfeng (China Chengxin Credit Rating Group)

24. Shen Yi (Tsinghua University)

25. Song Yingqi (IFS)

26. Sun Mingchun (Haitong International)

27. Sun Tianyin (Tsinghua University)

28. Wang Bolu (Tsinghua University)

29. Wang Junxian (China Institute of Finance and Capital Markets)

30. Wang Weiyi (Ping An Securities)

31. Wu Gongzhao (IFS)

32. Wu Qiong (Tsinghua University)

33. Wu Yue (Tsinghua University)

34. Xiang Fei (PICC Property and Casualty Company Limited)

35. Xiao Sirui (CEEX)

36. Yan Xu (Hwabao WP Fund)

37. Yang Li (IFS)

38. Yin Hong (ICBC)

39. Zhang Jingwen (ICBC)

40. Zhao Jiayin (IFS)

41. Zhu Yun (Tsinghua University)

Core Ideas

Carbon neutrality will have a positive impact on China's medium and long-term economic growth for several reasons. First, China will reduce its net energy imports during the transition to renewable energy sources. Second, large-scale investments in green and low-carbon industries will help boost economic growth. Third, the new job opportunities generated by the low-carbon sector may outweigh the job losses in high-carbon industries. Last, extensive R&D and application of green and low-carbon technologies can improve China's global competitiveness in industry.

Based on the models such as Energy Policy Simulator (EPS) and the scope consistent with the “Green Industries Guidance Catalogue”, the report predicts that China’s cumulative demand for green and low-carbon investments in the next thirty years will reach 487 trillion RMB (at constant 2018 prices).

As China endeavors to achieve carbon neutrality, both the demand and the supply of green finance will significantly increase. Financial institutions and market participants should seize the enormous opportunities created by carbon neutrality by improving governance mechanisms, clarifying goals of green development, disclosing more environmental information, and boosting product innovation.

High-carbon industries and companies will also face great pressures and risks during the transition to carbon neutrality, which will further spill over to the financial industry. Financial institutions should master methods for analyzing environmental and climate risks, level up risk disclosure, and develop innovative tools for climate risk management.

The report proposes to improve the policy framework for green finance with carbon neutrality as the goal by the following measures:

1) Revising green finance standards based on the "Do No Significant Harm" principle (DNSH)

2) Requiring financial institutions to calculate and disclose their asset carbon footprints and exposure to brown assets

3) Improving the capacity of financial institutions to analyze environmental and climate risks

4) Establishing stronger incentive mechanism for green finance to support low-carbon development

5) Encouraging sovereign wealth funds to engage in ESG investments

6) Ensuring the implementation of the “Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation"

7) Improving the regulatory mechanisms for carbon markets.

Abbreviated Edition

In September 2020, China’s President Xi Jinping made a commitment that China will peak its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. This pledge is a milestone in the global efforts to address climate change and a historic contribution to build a community with a shared future for mankind. We believe that the carbon neutrality goal will have profound implications for the model of China's economic growth. It will provide tremendous impetus for accelerating the green and low-carbon transition of the economy, as well as bring significant opportunities and challenges to the development of the financial industry.

The Green Finance Committee of the China Society of Finance and Banking (GFC) established a working group with more than 40 financial, economic and industry experts to conduct a research project titled “Roadmap for Financing China’s Carbon Neutrality”. The aim is to thoroughly assess the opportunities and challenges that carbon neutrality brings to the financial industry, as well as provide specific suggestions on improving the green financial system to attract social capital in achieving carbon peak and neutrality.

The project was launched at the end of 2020 and conducted in-depth analysis on various topics, covering the impact of carbon neutrality on the macroeconomy, industrial technology pathways and financial needs to achieve carbon neutrality, development opportunities of the financial industry brought by carbon neutrality, risks faced by the financial industry under the backdrop of carbon neutrality, and how to improve the policy framework of green finance with carbon neutrality as the goal. The project also provided numerous domestic and international cases and analytical methods as references, as well as suggestions for financial institutions and regulatory authorities.

This article is an abstract of the main viewpoints in the report, and the full version, approximately 200 pages, will contain more specific cases and background information.

1. Impact of Carbon Neutrality on the Macroeconomy

In the coming decades, it is essential for the main sectors of the real economy to undergo a profound, even potentially disruptive, transition, so that the goals of carbon neutrality and economic and social development could be achieved at the same time. Theoretically, the process of carbon neutrality and relevant policies have multiple mixed impacts on economic growth.

The positive impacts are that investments in renewables and other green industries will speed up, along with the decreasing costs of renewables and improved industry efficiency driven by endogenous technological progress. Many empirical studies have shown that advancements in renewables and green technologies can effectively improve total factor productivity (TFP) and economic growth. For instance,

Tugcu (2013), a professor in Turkey, found that renewable energy consumption positively contributes to TFP, with an elasticity between 0.7 and 0.8 in relation to GDP, while fossil fuel consumption has an elasticity between -1.7 and -2.1 with respect to GDP. [①]

Rath et al. (2019), based on panel data of 36 countries, found a positive relationship between renewable energy consumption and high TFP growth rates, and a positive correlation between fossil fuel consumption and low TFP growth rates. [②]

Yan et al. (2020), based on empirical research using provincial data from China, also discovered a significant positive link between renewable technology innovation and the productivity of China's green industries. [③]

However, the challenges coming along with the transition to carbon neutrality, such as stranded assets in high-carbon industries, periodic cost rise, and unemployment, will also have negative impacts on the macro economy. It may lead to bankruptcies in high-carbon industries, including fossil fuels, fuel-powered vehicles, steel, cement, etc., the abandonment of fixed assets and massive layoffs.

The direct economic costs of transition arise from the accelerated depreciation and elimination of fixed capital in high-carbon industries, which result in the early retirement of these assets, known as “stranded assets”.

Specific policy measures that contribute to the spiraling costs of high-carbon enterprises may include mandatory inclusion of emission-control companies in carbon trading mechanisms, carbon tax, carbon border adjustment taxes, and restrictions on the production or sale of high-carbon products.

Under these pressures, many jobs in high-carbon industries will disappear. Although green industries will create new job opportunities, many employees from traditional industries without skills makes it difficult for them to adapt to the requirements of new positions, resulting in "frictional" unemployment.

The abandonment of fixed assets and mass unemployment can lead to GDP losses due to “idle time of capital and labor inputs”

Whether the economies are able to absorb these impacts mainly depends on their economic structure, resource endowment and innovation capabilities. For example, some net exporters of fossil fuels may suffer from significant losses due to declining export of fossil energy. On the contrary, major energy importers, like China and Germany, will benefit from the global energy transition by substituting fossil imports with renewables. Vrontisi et al. (2019) found that by 2050, Europe’s domestic production of low-carbon technologies increases substantially, which can almost compensates the reduced demand for conventional fuels and equipment. [④] Additionally, due to the European Union's strong competitive advantage in the electric vehicles, it will take a larger market share globally, thereby further stimulating economic growth.

To some extent, the impact of carbon neutrality on the macroeconomy is also influenced by policies on carbon taxes, carbon pricing, green finance, and industry. Vrontisi et al. (2019) found that if carbon tax revenues are offseting by lowering the taxation on other goods and services, it can create a counter-balancing force to the increasing costs of production. As seen in Fragkos et al. (2017), if carbon tax revenues are used to reduce social security contributions, it can even raise overall employment levels. [⑥] However, policy uncertainty often negatively affects investment willingness in private sector and can have adverse impacts on the macroeconomy. Additionally, climate change policies adopted by some countries, such as Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), may also have negative implications for other countries.

The characteristics of China's economic structure and policy stance imply that China is more likely to achieve long-term growth benefits during this decarbonization transition.

First, China is a net importer of fossil fuels. Therefore, during the transition to renewables, it will significantly reduce its imports of fossil fuels, thereby lowering net energy imports. Calculations by Mercure et al. (2018) show that as a net importer of fossil fuels, China will be among the few major countries to benefit from low-carbon transition under the 2℃ climate policies scenario. [⑦]

Second, under the framework of the “1+N” decarbonization policies, China's demand for green and low-carbon investments in the next thirty years will reach trillions of RMB, which will help boost overall demand and GDP.

Third, the job opportunities created by low-carbon investments may significantly exceed the job losses resulted from the phase-out of high-carbon industries. Research by Garrett-Peltier (2017) found that on average, renewables and energy efficiency create 7.49 full-time-equivalent (FTE) jobs per $1 million investment, while the fossil fuels can only create 2.65 FTE jobs. [⑧]

Fourth, China has its advantages in large-scale R&D and low-carbon technologies. On one hand, China is a major manufacturing country, which allows for economies of scale and industrial cluster effects. On the other hand, China has the world's largest green product market, making it easier for R&D cost-sharing. Consequently, China is more likely to achieve technological progress and innovation in the field of green and low-carbon technologies, and its huge domestic market will help it become an important exporter of low-carbon technologies and products.

However, in the process of achieving carbon neutrality, China must also pay attention to its exposure of macroeconomic and financial risks.

First, if governments at all levels rely heavily on administrative measures to achieve the carbon peaking and neutrality goals, such as abruptly shutting down high-carbon companies or restricting their production in a “decarbonization frenzy”, it may lead to a significant supply drop in certain high-carbon industries, driving up energy and raw material prices, thus further posing risks of economic stagflation and unemployment.

Second, if high-carbon companies are not effectively empowered and assisted in low-carbon transition, a significant amount of high-carbon assets may become stranded and non-performing, or experience substantial valuation declines, thus leading to financial risks.

In conclusion, China should adopt more market-based approaches to promote low-carbon transition to realize its carbon peaking and neutrality goals. It should fully explore the macroeconomic benefits that energy transition, green investment, and technological progress can bring. China should strengthen its international market competitiveness in various green and low-carbon fields while keeping macroeconomic and financial risks associated with the transition under strict control.

2. Carbon Neutrality Pathways and Demand for Green and Low-carbon Financing

We have studied China's decarbonization pathways under two scenarios: the existing policy scenario and the carbon neutrality scenario, including the national and major industries' trajectories for carbon emissions. The existing policy scenario incorporates policies that have already been announced in China, including industry plans, strategies, and policy objectives issued since the proposal of the carbon neutrality target, as well as references to local planning outlines that have been introduced. The carbon neutrality scenario sets the goal of achieving carbon neutrality before 2060 and uses the “Energy Policy Simulation (EPS) model” as the primary analytical tool, combining policy measures based on international best practices (see Table 1). We expect that many of the measures listed in this carbon neutrality policy package will be included in the "1+N" roadmap currently being developed by the government.

Table 1: Combinations of policy measures under two scenario assumptions

Existing Policy Scenario | Carbon Neutrality Scenario | |

Overall | Carbon intensity down by 60%-65% from 2005 level. Striving to peak carbon emissions by 2030. System featured mainly by carbon intensity control and supplemented by controls on total emissions. Comprehensive implementation of the “Guiding Opinions on Accelerating the Establishment and Improvement of a Green, Low-Carbon, and Circular Development Economic System”. Energy intensity down by 13.5% during the 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP).

| Carbon emissions caped at around 10 billion tonnes by 14th FYP. Coal consumption to peak by the end of the 14th FYP. Total energy consumption not to exceed 5.5 billion tonnes of standard coal by 2025. Carbon pricing mechanism (including carbon emissions and carbon tax) to be implemented in all economic sectors. Significant reduction in carbon emissions by 2035 compared to peak levels.

|

Industry | Accelerate the green transition of energy-hungry industries, aiming for the energy resources and efficiency of major industrial products to reach international advanced levels around 2035.

| Based on the existing policy scenario, strengthen non-CO2 greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction policies. Improve manufacturing energy efficiency to meet international standards. Accelerate the electrification of fuels, hydrogen energy, industrial carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), and promote zero-waste manufacturing, etc.

|

Power | China’s power development aligns with its “Energy Supply and Consumption Revolution Strategy (2016-2030)”. Coal-fired power capacity to continue growing slightly during the 14th FYP period. Non-fossil energy to account for 25% of primary energy consumption by 2030. Total installed capacity of wind and solar power to reach 1.2 billion kilowatts (kW), in line with China's latest NDC. Hydrogen energy development to align with existing planning goals.

| Based on the existing policy scenario, accelerate the low-carbon transition of the power grid. Develop a timetable for the phasing-out of conventional coal-fired power plants (between 2040 and 2045) and vigorously develop hydrogen energy and high-proportion renewable energy (accounting for over 70% of electricity generation by 2050), etc.

|

Transportation | By 2035, of all new car sold in China, new energy vehicles (NEVs) accounts for 50%, eco-friendly vehicle models for the other half, aligning with the “New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan (2021-2035).”Keep the momentum of energy-saving and efficiency improvement in major transportation vehicles during the 13th FYP period. Development of public transportation meets the requirements of the national new urbanization strategy. Green freight also aligns with the requirements of the “Outline on building China's strength in transportation”.

| Based on the existing policy scenario, speed up new energy transportation development. All new car sold in China are EVs by 2035, while all are hybrid vehicles during the 14th FYP period. Optimize overall transportation planning, reduce freight demand, etc.

|

Construction | Currently, 50% of newly constructed buildings meet green building standards, and is steadily increasing during the 14th FYP period. Implementation of nearly zero-emission buildings (NZEBs) standards. Compliance with national policies regarding green refrigeration, heating, and other requirements.

| Based on the existing policy scenario, further increase the new buildings to all green during the 14th FYP period, and implement mandatory NZEBs standards. During the 15th FYP period, apply NZEBs standards to newly constructed buildings, electrify the energy use of living in the buildings, extend building lifespans, etc. |

Agriculture & Forestry | By 2030, forest stock volume to increase by 4.5 billion cubic meters compared to 2005, reaching 18.4 billion cubic meters. Comprehensively promote waste-free city and reduce food waste.

| Based on the existing policy scenario, improve forest quality and increase carbon sink capacity related to land use. Establish non-CO2 emissions reduction targets and policies for agriculture, optimize dietary structure, etc.

|

Source: Compiled by the Working Group

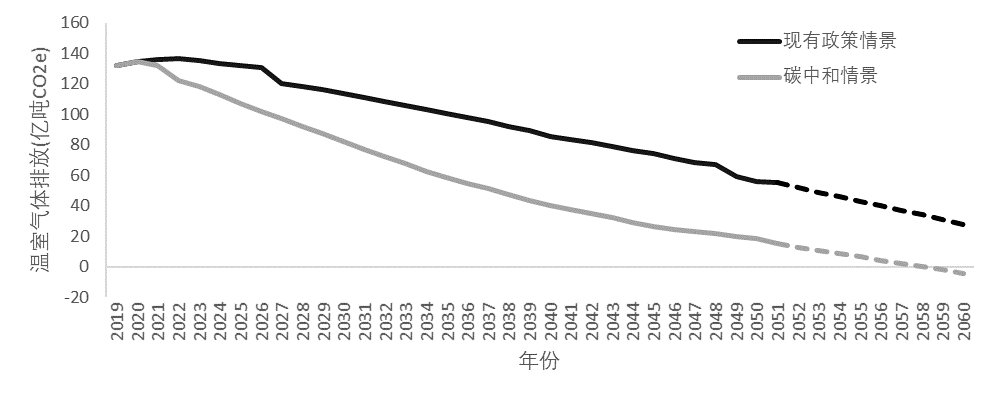

The analysis with our model shows that under the existing policy scenario, GHG net emissions, total emissions, and energy-related CO2 emissions can peak around 2025, respectively at 13.6 billion tonnes, 14.5 billion tonnes, and 10.4 billion tonnes, and steadily decline afterwards. By 2035, these emissions are expected to decrease to about 74%, 77%, and 81% of the 2019 levels. However, by 2060, GHG net emissions, total emissions, and energy-related CO2 emissions are projected to be 2.8 billion tonnes, 4.5 billion tonnes, and 2.2 billion tonnes, respectively, indicating that net-zero emissions have not been achieved.

Under the carbon neutrality scenario, GHG net emissions, total emissions, and energy-related CO2 emissions in China can reach their peak during the 14th FYP period. By 2035, they are projected to decrease to about 44%, 49%, and 48% of the 2019 levels. In 2050, these three kinds of emissions are estimated to be 18.41 million tonnes, 31.54 million tonnes, and 18.95 million tonnes, respectively, accounting for 22%, 14%, and 28% of the emissions levels in 2019. Following this trend, GHG net emissions are expected to achieve near-zero emissions by 2060 (see Figure 1).

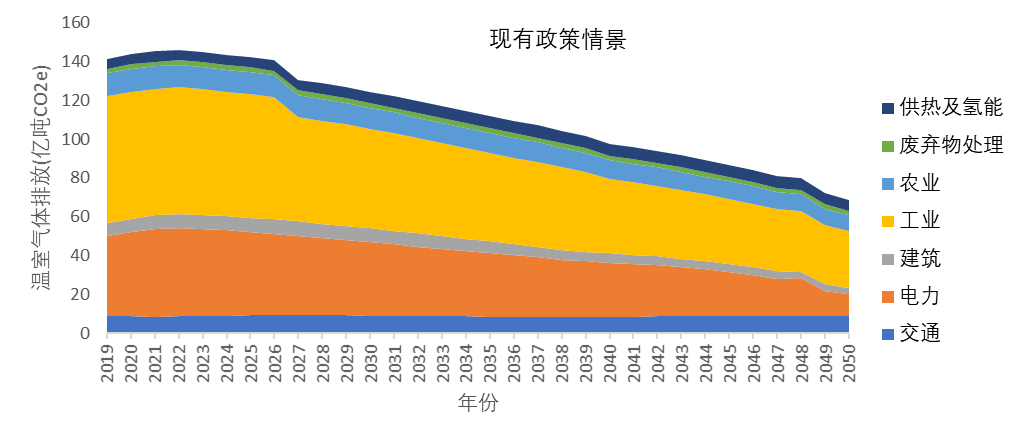

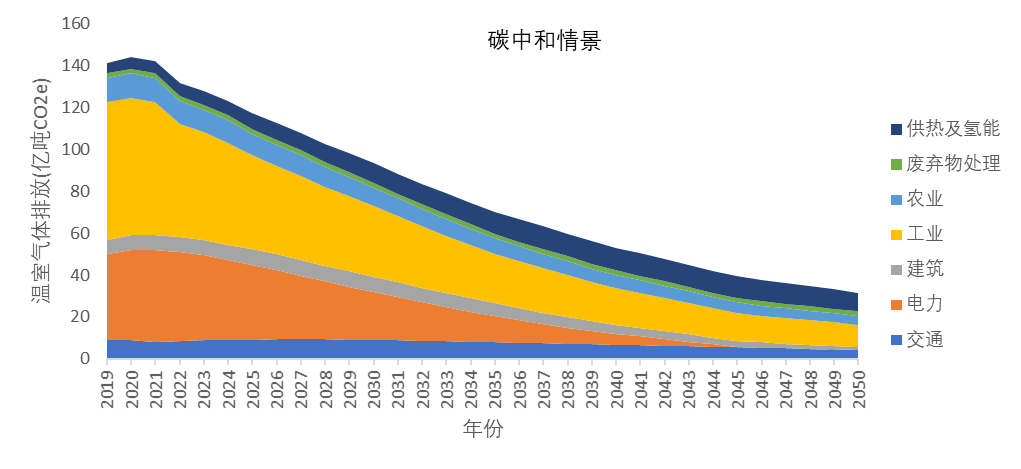

Through quantitative analysis of deep decarbonization pathways under the two scenarios, we believe that to achieve carbon neutrality goals, each sector needs to take the following measures:

Power: The power system must ensure its reliability before undergoing deep decarbonization. The main pathways include developing renewable energy, accelerating the phase-out of coal-fired power plants, and improving power system flexibility.

Industry: The green transition of the industry should focus on improving energy efficiency in industrial products and processes, optimizing industrial structure, exploring energy-saving potential in the system, and promoting zero-carbon pilot projects in the industry.

Construction: this sector needs to speed up the formulation and implementation of mandatory ultra-low energy consumption and zero-carbon building (ZCB) standards, apply energy-efficient appliances and facilities, control the overall building volume, and extend building lifespans.

Transportation: it is necessary to promote green and low-carbon urban planning, reduce the motorized travel demand, establish low-carbon standards for heavy-duty vehicles, and develop hydrogen-powered heavy-duty transportation.

Figure 1: Trends of GHG net emissions under the existing policy scenario and carbon neutrality scenario.

Note: The emission trends from 2020 to 2050 are based on the working group’s model, while the emissions from 2051 to 2060 are estimated with the extrapolated emission trends from 2041 to 2050.

Figure 2: Trends of GHG net emissions by sector under the two scenarios.

We also made predictions about the demand for green and low-carbon investments in China over the next thirty years (2021-2050) with the aim to achieve carbon neutrality. The methodologies and steps are using the EPS model to estimate the investment required for the application of low-carbon energy systems in various sectors, estimating the demand for environmental and ecological investments in the future based on recent historical data and GDP proportions, and converting the predicted investments from the “model-based statistical scope” to the “report-based statistical scope” based on the “Green Industries Guidance Catalogue”.

Our conclusion is that under the carbon neutrality background, according to the “report scope” calculation, the cumulative demand for green and low-carbon investments in China over the next thirty years will reach 487 trillion RMB (at constant 2018 prices). This predicted value is significantly higher than the estimates provided by Tsinghua University's Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, Goldman Sachs, and CICC reports [⑨]. The difference between our predictions and those of these institutions lies mainly in the scope of data used. For example, our data covers over 200 green industry sectors (including not only low-carbon investments but also environmental and ecological investments), while the above-mentioned institutions primarily cover a much more limited scope of low-carbon investments.

Table 2: Comparison of estimated results and scopes for various green and low-carbon investment demands (Unit: CNY)

Tsinghua Univ.

| Goldman Sachs

| CICC | Our Working Group (GFC) | |

Estimated Value | 174 trillion | 104 trillion | 139 trillion | 487 trillion |

Forecast Period | 2020-2050 | 2021-2060 | 2021-2060 | 2021-2050 |

Scope of Industries Covered

| Low-carbon energy-related sectors, excluding ecological and environmental protection

| Low-carbon energy-related sectors, excluding ecological and environmental protection

| Low-carbon energy-related sectors, excluding ecological and environmental protection

| Based on the 211 sectors in the “Green Industries Guidance Catalogue”, including low-carbon energy system-related sectors as well as ecological and environmental protection |

Does it include working capital in addition to fixed asset investments?

| Only includes fixed asset investments

| Only includes fixed asset investments

| Only includes fixed asset investments

| Includes both fixed asset and working capital requirements

|

Does it cover the entire investment for low-carbon and green projects, or only the additional costs for the green components?

| Emphasizes the additional costs for generating green benefits in the projects

| - | - | In sectors such as construction and transportation, it includes all investments

|

Note: "-" indicates that the original report did not specify.

3. How the financial industry can seize opportunities of carbon neutrality

In the next thirty years, the goal of carbon neutrality will provide impetus for developing green finance, thus creating great opportunities for financial institutions.

On the demand side, it means that the government will introduce a series of more aggressive policies and measures to support low-carbon projects. These policy measures include launching and expanding the national carbon trading market, providing subsidies and tax incentives for green and low-carbon activities, implementing financial incentives to lower the financing costs of green projects, and supporting green production and consumption in industries such as energy, transportation, construction, and manufacturing.

On the supply side, expected green finance policies, including central bank's tools for decarbonization, green banking assessment mechanisms, environmental disclosure requirements, risk weight adjustments, green project guarantees and subsidies, will all improve the returns of banks and other financial institutions, which in turn push them to offer more green financial products and services.

With concerted efforts from both the demand and supply sides, the green finance market will continue to expand rapidly.

We have discussed the progress, opportunities, and challenges faced by China's green finance in seven major areas: banking, capital markets, insurance, institutional investors, carbon market, financial technology (fintech), and transition finance. For each area, the report also reviews relevant international experiences and put forward a series of suggestions to improve the policy environment, corporate governance, information disclosure, and product innovation.

3.1. Banking

In recent years, the overall domestic banks have achieved significant development in green finance, with rapid growth and high-quality assets.

According to statistics from the People's Bank of China (PBC), as of the end of 2020, the balance of green loans denominated in both domestic and foreign currencies in China reached 11.95 trillion RMB, an increase of 20.3% compared to the beginning of the year. Among them, the balance of green loans to enterprises reached 11.91 trillion RMB, accounting for 10.8% of loans to enterprises and institutions during the same period. The balance of green non-performing loans (NPL) nationwide was 39 billion RMB, with a NPL ratio of 0.33%, which was 1.65 percentage points lower than the NPL ratio of enterprises.

Since the beginning of 2021, the growth rate of green loans has further accelerated. As of the end of June 2021, the balance of green loans denominated in both domestic and foreign currencies reached 13.92 trillion RMB, a year-on-year increase of 26.5%, 14.6 percentage points higher than the growth rate of all types of loans.

We believe that the huge demand for green and low-carbon investments in the context of carbon neutrality will continue to increase the proportion of green loans in the overall loan portfolio.

The leading financial institutions in China have made many attempts in terms of strategy planning, product innovation, and risk management related to carbon neutrality. Some domestic cases are as follows

Strategy Planning: The ICBC's “2021-2023 Development Strategic Plan” sets goals, pathways, and tools to build a green finance system. By implementing measures such as industry-specific green loan policies, supporting economic capital occupancy, authorization, pricing, and scale, the bank aims to advance the dual carbon work with “four pillars”, i.e. developing low-carbon industries, promoting low-carbon transition of investment and financing portfolios, strengthening climate risk management, and laying a foundation for carbon measurement in investment and financing.

Financial Products Innovation: Many banks have launched various green loans for clean energy, energy conservation, green transportation, low-carbon construction, and NEVs. Some have started to offer ESG wealth management products, and Bank of Huzhou has introduced carbon allowance collateral and pledge.

Risk Management: ICBC has conducted environmental stress tests on high-carbon industries such as thermal power and cement by making partial disclosures. ICBC, Industrial Bank, Bank of Jiangsu, and Bank of Huzhou have taken the lead in environmental information disclosure, including decarbonization information for green projects. Some banks have disclosed their own operational carbon emissions, while others try to calculate the carbon emissions of their financially-supported projects.

Based on these practices above, in August 2021, the PBC issued the first batch of domestic green finance standards, including the “Guidelines on Environmental Information Disclosure of Financial Institutions” (JR/T 0227-2021) and the “Environmental Rights Financing Tools” (JR/T 0228-2021).

However, considering the requirements to achieve carbon neutrality and comparison with international best practices, many banks in China, especially small and medium-sized banks, still have gaps in governance frameworks, strategic goals, implementation pathways, carbon footprint calculation, climate risk analysis, environmental information disclosure, and product innovation capacities. Therefore, we suggest that banking institutions in China should make improvements in the following areas,

Develop strategic plans compatible with the goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, and strengthen governance mechanisms;

Make clear definition on brown assets, calculate the carbon intensity and footprint of bank assets, and improve information disclosure;

Conduct scenario analysis and stress tests for climate-related risks;

Increase support for green projects and clients, assist clients in high-carbon industry during low-carbon transition, reduce the risk exposure of brown projects and clients in investment and financing;

Improve the capacity for innovative green financial products and services, such as green loans and green wealth management products linked to carbon footprints, carbon allowance collateral and pledge, carbon revenue-backed notes, and financial consultant on carbon trading.

3.2. Capital Markets

In China, capital market financing for green industries has become an important part of green finance. During the 13th FYP period, green low-carbon industries such as new energy, energy conservation and environmental protection have raised a cumulative capital of about 1.9 trillion RMB through initial public offerings (IPOs), refinancing, listing, and issuance of corporate bonds. The scale of green corporate bonds issuance on the exchange market was approximately 290 billion RMB. The number of listed companies in green and low-carbon industries such as new energy, new materials, energy conservation, and environmental protection was six times that of energy-intensive industries like iron and steel, cement, and electrolytic aluminum, with their total market value being three times higher. [11]

By the end of 2020, China had issued a total of about 1.3 trillion RMB green bonds, ranking second globally in terms of green bond balance. In the first half of 2021, the issuance of green bonds in China has surpassed the total of the previous year. As of the end of June 2021, China had a total of over 270 funds consisting of ESG-themed and ESG investment strategy portfolios, with a total assets under management (AUM) of 300 billion RMB.

In addition, ESG information disclosure by listed companies in China is on the rise. In 2020, about 27% of the listed companies published ESG reports and 289 companies disclosed information in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards. Among the constituents of the CSI 300 Index, 259 companies have released independent ESG reports with high-quality disclosure.

Since 2021, the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII) and the stock exchanges have launched carbon neutrality bonds. In the first half of the year, 111 carbon neutrality bonds were issued with a total scale of about 126 billion RMB. So far, there are no defaults on green bonds yet. On March 18, 2021, the NAFMII issued the Notice on Clarifying Mechanisms in Relation to Carbon Neutrality Bonds, outlining the areas where green bonds must satisfy requirements, including funds usage and management, project evaluation and selection, and information disclosures.

From international experience, the efforts of more mature capital markets in developing green and sustainable finance mainly focus in three following aspects.

First, to improve market transparency with more information disclosure related to sustainability, including ESG information and climate-related financial disclosure framework recommended by Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

Second, promote the innovation of green financial products, such as green bonds, climate bonds, sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), green asset-backed securities (ABS), carbon futures, etc, to meet the requirements of various market players for green and low-carbon transition.

Third, strengthen the institutional investors’ preferences for green and sustainable investments. For example, the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) recommended in 2019 that its member institutes incorporate sustainable investment standards and ESG as investment analysis factors into portfolio management (such as pension funds, foreign exchanges reserves, etc.).

By the end of 2020, there were 3,038 institutions globally that had signed the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI), involving assets of approximately $103.4 trillion.

To achieve the goal of the carbon neutrality, the greening of China's capital market still faces several challenges.

First, the environmental and climate-related information disclosure by listed companies is still underperforming in quantity and quality. The main reason is the lack of disclosure guidelines or standards and a unified calculation methodology for certain indicators. Besides, many companies have not established internal mechanisms to collect some core data.

Second, there are few domestic funds and financial products with a preference for green investments.

Third, the investors’ awareness in exercising their shareholder rights needs to be further raised.

Fourth, the product innovation capacity of major participants in the capital markets, such as security firms, still needs to be improved.

Fifth, there is a lack of financial derivatives related to carbon emissions trading, such as carbon futures, carbon swaps, and carbon options.

We suggest that all participants in the capital market further playing the key role of capital in the green transition of industries. To be more specific,

The regulators should promptly release guidelines or standards for the climate-related information disclosure by listed companies and bond issuers, improve the regulations on the use of funds raised by green bonds, and establish a self-regulation mechanisms to regulate third-party green bond assessment and certification.

Asset management organizations should launch more investment products incorporating ESG factors, strengthen the disclosure of their own environmental and climate-related information, actively exercise shareholder rights, and push for the green transition of invested enterprises.

Security underwriters and trading intermediaries should also pay attention to the ESG performance of issuers, guide the market to achieve differentiated pricing, strengthen product innovation capacities, and launch more products that support decarbonization. It is advisable to launch carbon futures products as soon as possible to offset the market risk, and establish a standardized carbon financial market. It is encouraged to be actively participated in the development of international standards for climate-related information disclosure.

3.3 Insurance

Green insurance is an insurance solution proposed to support environmental improvement, address climate change, and promote the efficient use of resources in the process of green development. Green insurance in a broader sense also includes the green utilization of insurance funds. From the perspective of insurance companies’ liabilities, the products and services are categorized as follows,

Environmental improvement-related: environmental liability insurance;

Climate change-related:

Addressing physical risks: catastrophe insurance, forest insurance, agricultural insurance;

Addressing the low-carbon transition risks: liability insurance, guarantee insurance, etc., that are provided to companies and projects in non-fossil energy, NEVs, green buildings, green infrastructure and other areas.

This section will discuss green insurance services related to climate change, with a focus on carbon neutrality.

In recent years, under the guidance of policy documents, such as “Guidelines for Establishing the Green Financial System”, issued by seven government agencies, regulators have actively promoted the construction of a green insurance policy system.

In December 2019, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) issued the “Guiding Opinions on Promoting High-Quality Development of the Banking and Insurance Industries”, proposing to explore innovative green financial products, such as environmental pollution liability insurance, and climate insurance. Industry self-regulatory organizations, such as the Insurance Association of China (IAC) and the Insurance Asset Management Association (IAMAC), endeavors to the research and innovation of green insurance products.

In terms of addressing physical risks caused by climate change, many insurance companies have launched products such as catastrophe insurance and agricultural insurance. For example, pilot programs on natural disaster catastrophe insurance and public catastrophe insurance have been conducted in regions like Shenzhen, Ningbo, Guangdong, and Chongqing.

In addition, the premium scale of agricultural insurance in China's green property insurance has been increasing up to 30%. Weather index insurance is a typical type in agricultural insurance addressing the physical risk caused by climate change. It has been developed various insurance products tailored to local conditions, empowered by technology for risk management, and combined with assistance to farmers and poverty alleviation.

In terms of addressing the risks in low-carbon transition of economy, some insurance companies in China tries to provide innovative green insurance products for green buildings, PV generation, and green technology and equipment industry. For example,

PICC P&C developed green building performance insurance in Beijing, Qingdao and Huzhou, and launched a pilot product named “Jian Tan Bao” (meaning Carbon Reduction Insurance) in Qingdao for energy-efficiency reconstruction of buildings;

Ping An Insurance provides guarantees for decarbonization renovation and upgrading projects of cement companies in Guangdong;

Some insurers have developed renewable energy insurance and services to solar PV, wind and hydro power facilities, such as China Pacific Property Insurance (CPIC Property) provides water level and other natural disaster warning services through its risk radar client end and Internet of Things (IoT).

Under the guidance of IAC, the insurance industry also begun to explore NEVs insurance.

To address the transition risks, some insurance companies have also introduced carbon insurance, which mainly covers risks in carbon financing and carbon delivery, to mitigate carbon pricing risk faced by carbon emission trading enterprises.

Besides, in the area of ecological carbon sinks, the insurance industry have established a function model for measuring forestry damage and carbon sequestration capacity. For example, in Fujian Province, PICC P&C has launched the innovative products including “Carbon Sink Loan”, the bank loan-based forest fire insurance, and “Forestry Carbon Sink Insurance”; China Life P&C has introduced the “Forestry Carbon Sink Index Insurance”.

With the standards of carbon assets pledge take shape, some insurance companies have also begun to explore guarantee insurance for carbon assets pledged loans.

In recent years, China’s green insurance have seen progress, but there is still a big gap to meet the demands for guaranteeing the green transition of economy and society. More efforts are needed in the product supply, insurance coverage, accumulation of risk data, innovation incentive mechanisms, and other aspects.

First, it is necessary to push for the innovation of insurance products and services, improve their coverage and variety, and build a green insurance products and service system applicable for different scenarios and industries.

Second, we will strengthen the accumulation of green insurance-related data, enhance cooperation with all sectors of the community, and apply blockchain, big data and other technologies to support the innovation, rate-setting, underwriting and claims handling, and risk management services.

Third, developing risk assessment standards and risk management service specifications for key industries, and further improving the capacity building in the insurance industry for climate and environmental risk management.

Fourth, it is suggested that government departments should guide the use of insurance market mechanism for risk management in relevant industries, by encouraging companies’ participation with premium subsidies and tax incentives, and insurers to develop customized products with differentiated pricing.

3.4 Institutional Investors

Domestic institutional investors in China primarily include sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, insurance asset management companies, mutual funds, and private funds. In recent years, domestic institutional investors have actively explored ESG investments under the guidance of regulatory authorities, and gradually conducted capacity building. For example, in the 2018 annual report, China Investment Corporation (CIC) outlined its commitment to sustainable development factors like ESG while pursuing financial returns. The National Council for Social Security Fund (NCSSF) provided an analysis and understanding of its social responsibility investment strategy in its 2017 report titled “Research on Social Responsibility Investment Strategies”, highlighting the use of three investment strategies: social screening, shareholder engagement, and community investment. Some insurance companies in China have also incorporated environmental and climate-related factors into their investment principles, investment strategies, and comprehensive investment evaluation processes. They refrain from investing in or divest from non-compliant companies, while actively using insurance funds to provide financing support for green projects. For example, Ping An Group disclosed its sustainable insurance strategy and responsible investment strategy based on a review of various ESG issues within the group in its “2018 Climate Change Report”. The report also provided specific information on how climate and environmental factors are integrated into investment decision-making.

In recent years, China's mutual funds have been developing green and sustainable investments, with a rapid increase in the number of funds adopting ESG investment principles. According to Wind, as of August 2021, there were a total of 183 ESG-themed funds in China, with a combined total AUM exceeding 213 billion RMB. As of August 18, 2021, a total of 69 institutions in China had signed the UN PRI. Among the major mutual fund companies that have signed are China Asset Management, E Fund Management, Harvest Fund Management, Penghua Fund Management, Hwabao WP Fund Management, China Southern Fund Management, Bosera Fund Management, Morgan Stanley Huaxin Fund Management, Da Cheng Fund Management, China Merchants Fund Management, Aegon-Industrial Fund Management, China Universal Asset Management, and YinHua Fund Management.

Since the publication of the "Green Investment Guidelines (For Trial Implementation)" by the Asset Management Association of China (AMAC) in November 2018, mutual fund management companies have made improvements in institutional personnel allocation, establishment of green investment strategies, and optimization of asset portfolio management. According to the Fund Manager’s Green Investment Self Assessment conducted by AMAC in 2020, about 80% of mutual fund institutions have conducted green investment research and established green evaluation methods and databases.

Private fund institutions are also exploring green investment strategies, conducting research on green investment, and establishing green investment systems. According to the assessment by the AMAC, approximately 40% of private fund management institutions have conducted green investment research, and about 27% of them have established pre-investment green assessment mechanisms or due diligence processes.

However, compared to the requirements of carbon neutrality and international best practices in sustainable investment, the capacity building of many domestic investment institutions for sustainable investment is still in the early stages. There is a lack of comprehensive investment concepts and clear strategies in climate change or ESG investment. Few institutions actively engage in ESG investment and disclose environmental-related information. The proportion of assets aligned with ESG principles remains low. There are several reasons behind the shortcomings: 1) the absence of an authoritative ESG rating system and standardized disclosure practices in China; 2) improvement in capacity building and system development of research on green investment, as well as diversification and scaling up of product portfolio;

3) absence of data and risk management standards, as well as investor education on ESG.

This report suggests that China’s institutional investors should integrate the concept of sustainability into their governance mechanisms. They should speed up the development of green investment and research systems, establish professional teams, and turn the carbon neutrality vision into asset allocation and decision-making actions. Meanwhile, there should be an emphasis on environmental and climate-related information disclosure to promote the diversification and scaling up of green investment products.

To be more specific, institutional investors are recommended to,

Establish a dedicated sustainable investment committee within the organization to develop sustainable investment strategies;

Use multi-scenario analysis to evaluate the climate-related risks and opportunities in asset allocation;

Set the weighting of main asset classes in the portfolios with the investment trajectory based on net-zero emission pathway;

Use indicators such as carbon intensity of assets, exposure to high-carbon assets, and the proportion of green/zero-emission assets to evaluate the sustainability of asset portfolios, with corresponding information disclosure;

Improve ESG evaluation and selection methods for target companies, and take ESG factors into consideration in the due diligence process to evaluate the impact of ESG-related risks on the companies.

Institutional investors should also exercise their shareholders’ query and voting rights, to urge the invested companies to speed up green transition, improve their ESG performance, and consider low-carbon and other sustainable factors in major decision-making.

Besides, the investment, social and environmental values of ESG and carbon neutrality products can be better understood through forums and regular strategy reports on ESG.

3.5 Carbon Market and Carbon Finance

Since 2011, China has launched carbon emissions trading pilot programs in seven provinces and municipalities, including Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Guangdong, Hubei, and Shenzhen. As of the end of June 2021, the pilot carbon market has covered more than 20 industries, including power, steel, and cement, with nearly 3,000 key emitters. The cumulative transaction volume of carbon allowance reached approximately 480 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, with a total transaction value of 11.4 billion RMB. On July 16, 2021, the national carbon emissions trading market was launched, with the power generation industry being the first industry to be included. A total of 2,225 power generation companies and captive plants participated the market, with a quota scale exceeding 4 billion tonnes per year. This marked the formal establishment of world’s largest market in terms of GHG emissions. According to the plans released, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment will gradually expand the market coverage, enrich trading varieties and methods, and achieve stable and effective operation and healthy and sustained development of the national carbon market, based on the stable operation of the carbon market in the power generation industry.

Although China’s emissions trading scheme (ETS) is world’s largest in terms of volume of allowances, it still faces some issues and challenges compared to mature carbon markets. These include the differentiation between the national ETS and regional markets, the full utilization of the financial attributes of the carbon markets, the optimization and improvement of allowance allocation plan in the national ETS, clear rules for carbon offset mechanisms in the carbon market, and solutions to trading methods, participants, and liquidity in the carbon market.

In carbon finance, although institutional investors are allowed to participate in regional carbon markets in China, not many of them are actively participating due to the non-standard characteristics of carbon emissions permits. Besides, their involvement is mainly limited to traditional bank account opening and fund settlement, rather than market-maker mechanism aiming to improve market functionality, carbon-related financing and asset management, and innovative trading product development. These patterns can be attributed to a lack of awareness regarding the significance of the carbon market in pricing and guiding low-carbon investment, as well as insufficient performance in key market factors such as liquidity, price signal and its fairness, and market scale. The market of carbon financial products and derivatives is not well-established.

The non-standard product of carbon emissions permits has also restricted the participation by financial institutions, and regulatory requirements significantly increase the difficulty for traditional financial institutions such as banks, securities, and insurance companies to step into the carbon market.

We recommend accelerating the expansion of the industry coverage of the national ETS. In addition to the power sector, we should swiftly bring in industries such as petrochemicals, chemicals, construction materials, steel, non-ferrous metals, paper-making, and aviation into the national ETS. We should also expedite the expansion of GHG coverage in national ETS, putting methane under regulation.

We should continue to leverage the role of pilot carbon markets and encourage further institutional and mechanism innovations. For instance, we can explore carbon market designs under a cap-control framework. We should strengthen the design of paid allowances and offset mechanisms, and implement paid and differentiated allocation of allowances in a timely manner.

We should place the financial attributes of carbon market in an important position during its development, and strengthen innovation in carbon finance and derivatives products. For example, in the national ETS, we can explore carbon allowance (voluntary emission reductions, VERs) collateral/pledge financing, allowance repurchases and carbon bonds, and accelerate the introduction of carbon futures and options, among other carbon finance derivatives.

We should also encourage the participation of financial institutions and investors into the national ETS, and expand the sources of funding for transition enterprises.

We should encourage individuals to participate in the carbon market through VERs and carbon-inclusive initiatives, converting low-carbon actions such as green transportation, afforestation, energy conservation, and clean energy use into economic benefits.

We should also enhance capacity building for various market entities, and establish new regulatory mechanisms for the carbon market, which will leverage the advantages of self-regulation and social supervision of government departments, exchanges, third-party organizations, and industry associations.

3.6. Financial Technology (Fintech)

In the pursuit of carbon peak and carbon neutrality, fintech can empower green finance and green development in various aspects such as green asset identification, certification and traceability, risk and energy efficiency management, information disclosure, and shared platforms. Developed countries have already established platforms for green asset trading, clean energy trading, and individual sustainable investments based on digital technology. On December 9, 2020, PBC Governor Yi Gang mentioned in his speech at the Singapore FinTech Festival that PBC would embed fintech into green finance. With the support of regulatory authorities, some innovative cases have emerged in China. For example, Huzhou has established technology-empowered green finance platforms like “Lv Dai Tong” (Green Loan Pass) and “Lv Xin Tong” (Green Credit Pass), and Chongqing has a comprehensive green finance big data service platform, all of which have functions such as granular data collection for green loans, intelligent identification of green projects, and measurement of environmental benefits. Ping An Bank's “Ping An Green Finance” big data intelligent engine integrates cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data, cloud computing, the IoT, and blockchain, enabling real-time monitoring of multidimensional data on the environment, pollution sources, weather, environmental impact assessments, public complaints and proposals, and public opinion. Insurance companies like PICC P&C have efficiently processed claims by using big data, modern surveying, and geographic information technology to generate catastrophe insurance flood maps. In addition, some institutions have started using fintech to collect ESG data to support customer ESG evaluations.

Internationally, fintech has been widely used in green and sustainable finance. Innovative cases include the use of blockchain technology to establish carbon offset project markets and to support green bond issuance, the use of AI technology to build solar energy trading platforms, mobile applications to help individual investors participate in green investments, and the use of satellite data to support carbon trading platforms. These practices provide great references for domestic institutions.

Although China has made rapid progress in using fintech to support green finance in recent years, there is still significant room for development compared to the potential demand generated by the carbon peak and carbon neutrality goals. For example, in the future, all companies and financial institutions participating in carbon neutrality will need to conduct carbon accounting. Most green production processes, products, consumption, and services will require labeling. Financial institutions engaging in comprehensive green finance business will need to use more digital technologies in risk control, customer acquisition, and cost control. Regulatory authorities will also need to increase research and application of relevant technologies in implementing green standards, strengthening statistics, monitoring climate, and conducting climate risk analysis.

We suggest that technology companies and financial institutions further expand the application of fintech in green finance through the following aspects,

Use fintech to identify, label, and measure the environmental benefits of green assets.

Utilize big data, AI, and cloud computing to manage data reporting, statistical analysis, performance evaluation, and risk monitoring in green finance operations.

Conduct environmental monitoring and early warning through big data platforms.

Enhance customer identification and penetration capabilities by leveraging AI to develop comprehensive green profiles for corporate or individual clients.

Utilize blockchain technology to record underlying asset in supporting the issuance of green and low-carbon thematic products.

Leverage the IoT and blockchain to acquire and record data on individual green and carbon reduction consumption behaviors, forming individual carbon credit profiles and promoting green and low-carbon behaviors.

Use big data and AI to push green and low-carbon wealth management products to customers with these preferences.

3.7. Transition Finance

Numerous high-carbon enterprises need to transit to low-carbon or zero-carbon businesses to achieve carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. However, these transition activities require investments in new technologies, equipment, manpower, and land resources. If these companies, which currently belong to high-carbon industries, are unable to obtain financing, the transition will become challenging and lead to potential consequences: enterprise that encountered capital chain rupture will result in bad loans for banks and affect financial stability; business closures and layoffs will hit social stability; and forced maintenance of high-carbon operations due to an inability to transition will lead to increased carbon emissions. In other words, effective transition finance arrangements can help enterprises quit high-carbon operations, accelerate their low-carbon transition, and mitigate financial and social risks.

Currently, both domestic and international green finance standards and policy frameworks do not fully encompass transition finance and may even “crowd out” transition finance. For example, while the current green credit guidance and green bonds catalogue in China do include some projects that support transition, the number and categories of such projects are limited, and many projects suitable for transition are not included in the green catalogs. Additionally, the working capital used to support low-carbon transitions and funds for acquiring high-carbon enterprises with the goal of promoting their transition (not project financing) cannot obtain support from green finance. Due to the lack of definitions and disclosure standards for transition enterprises and pathways, even if a company has a strong willingness and specific transition projects, many banks and capital market participants, considering the “greenwashing” risks, are reluctant or hesitant to provide financing, let alone green financing.

We propose the following aspects to promote the establishment of a framework that supports transition finance:

1) Clarify transition technology pathways and develop standards for transition finance. These standards should specify which industries or economic activities transition finance should support, identify the main transition technology pathways for these industries, and set appropriate quantitative entry thresholds, such as minimum emissions reduction targets.

2) Establish a system for transition certification and information disclosure. Transition finance activities should require the financing parties to disclose information such as the use of funds, the implementation of transition pathways, the achievement of transition goals (including carbon emissions and carbon intensity of companies or projects), environmental benefits generated (including emission reductions), and potential risk factors as well as their corresponding measures.

3) Innovate transition finance products to meet the financing needs of different transition pathways. Financial products involved in transition activities may include transition M&A funds, transition loans, transition bonds, transition guarantees, debt-to-equity swaps, and other financing instruments and arrangements.

4) Establish appropriate incentive mechanisms. The incentives include land resources for clean energy development provided by the government and regulatory authorities, renewable energy consumption quotas, subsidies, tax incentives, guarantees, and financial instruments to support carbon emission reductions.

5) Establish a national transition fund. Central government could establish a national green transition fund which specifically provides financing support for key industries and key regions that need to undergo green and low-carbon transitions.

4. How the Financial Industry Analyzes and Manages Climate Risks

Climate risks include physical risks and transition risks. Under the context of carbon neutrality, transition risks may lead to major financial risks. Financial institutions should strengthen the identification, quantification, management, and disclosure of climate-related risks, particularly transition risks. Based on domestic and international experiences, commercial banks, which primarily engage in lending business, tend to focus on assessing the impact of climate factors on credit risks; insurance companies, from the perspective of underwriting business, estimate losses and price insurance with catastrophe models; asset management institutions and investment departments in banks and insurance companies evaluate the impact of climate risks on asset valuation, investment portfolio returns, and other indicators.

Various methods and models are used in climate risk analysis to analyze how climate risks cause financial risks. The tools, methods, and models currently used by various institutions are extensive, including Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), catastrophe models (CAT Models), default rate models, valuation models, input-output models, multi-factor weighted models, and etc,. Several research institutions and financial institutions in China, such as Tsinghua University, ICBC, Industrial Bank, and Bank of Jiangsu, have conducted stress tests of transition risks, which are resulted from climate and environmental policies and technological progress, on industries such as coal-fired power, steel, cement, pharmaceuticals, and construction. For example,

The team from Tsinghua University calculated the default rate changes of coal-fired power companies under the context of carbon neutrality, and analyzed the impact on mortgage default rates caused by climate change-induced increased typhoon intensity in China’s coastal areas.

ICBC conducted research on carbon trading-related stress tests, analyzing the impact of four factors, i.e. carbon price, industry baseline, proportion of paid distribution, and application of emission reduction technologies—on corporate finance and bank credit risks.

Industrial Bank evaluated the impact of factors such as environmental protection policies and carbon quota prices on the credit risk of assets in the green building industry, using both the optimized traditional net present value method and the environmental stress testing method centered around risk models.

Bank of Jiangsu incorporated enterprise surveys and internal customer credit rating models to analyze the impact of factors such as policy factors, water risks, and carbon tax risks on credit ratings and default rates of the pharmaceutical and chemical companies.

Internationally, NGFS published the “Case Studies of Environmental Risk Analysis Methodologies” in September 2020, which includes methods and tools for environmental and climate risk analysis developed by over 30 global institutions. [12]

Financial institutions should disclose the identified and quantified climate risks appropriately. Risk disclosure with high comparability can optimize market transparency, improve market efficiency, and provide a basis for risk management. Five framework-and standard-setting institutions of international significance, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the GRI, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB),and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), published a joint statement of intent in September 2020, to set the frameworks and standards for sustainability disclosure, including climate-related reporting, along with those proposed by the TCFD, and work towards aligning existing standards with TCFD recommendations. As of now, more than 2,300 organizations have expressed their support for the TCFD recommendations. Some international financial institutions have disclosed information such as the carbon intensity (carbon footprint) of their loan and equity portfolios, implicit warming trends, carbon emissions of their operations, and climate stress test results under different scenarios.

China have proactively participated in global climate-related disclosure efforts and has organized domestic financial institutions to conduct relevant pilot projects through initiatives such as the UK-China Climate and Environmental Information Disclosure Pilot and local trials, which include disclosing environmental and climate risks. The G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, co-chaired by China, is also exploring establishing global disclosure standards for sustainability-related information based on the TCFD framework. In December 2020, Governor Yi Gang stated the need to establish a mandatory environmental information disclosure system for financial institutions. On July 28, 2021, the PBC issued the “Guidelines for Financial Institutions Environmental Information Disclosure” (hereinafter referred to as “Guidelines”) on behalf of the China Financial Standardization Technical Committee. The Guidelines recommend disclosing the impact of environmental factors on financial institutions, including environmental risks and opportunities, as well as quantified analysis of environmental risks. The first part of the Guidelines suggests disclosing the impacts of short-term, medium-term, and long-term environmental risks and opportunities on the institutions’ business and strategy, as well as the institutions’ responses to these impacts. The second part recommends the institutions disclose the status and plans of their scenario analysis or stress testing, as well as the methodologies, models, tools, conclusions, and actual implementations.

Management of identified climate-related risks is still a relatively new topic for domestic and international regulatory agencies and financial institutions. Some preliminary practices in recent years have indicated that financial institutions' climate risk management measures can include:

1) Establishing governance mechanisms and management frameworks for climate risks. Financial institutions can set up climate risk management committees at the board level, categorize and identify climate-related risks, establish and update relevant internal policies, and enhance methods and tools for risk measurement.

2) Setting specific targets to reduce exposure to climate risk. Targets related to climate risk mitigation can be expressed as reducing the proportion of brown assets to total assets over the next 5 or 10 years, or reducing the carbon intensity or footprint of assets (including equity investments, loans, and bond investments); risk control departments could set internal targets of gradually decreasing the Value at Risk (VaR) of high-carbon and high-risk assets.

3) Enhancing pre-lending/pre-investing risk assessment. Review procedures related to climate risks can be added to the existing due diligence process, high-risk clients and projects should be reviewed by qualified third parties, and raise the approval level for clients and projects with high climate risk.

4) Adjusting risk weights based on climate risks. Some financial institutions are exploring the practice of adjusting internal risk weights based on the “greenness” of assets. The institution can lower the risk weights of green assets and increase the risk weights of brown (high-carbon) assets, while maintaining its overall capital adequacy ratio. This encourages lending or asset allocation towards green assets while constraining exposure to high-carbon industries.

5) Enhancing post-lending/post-investing climate risk management. Financial institutions can strengthen post-lending/post-investing risk monitoring, promote the transformation of existing assets to low-carbon alternatives, and utilize hedging instruments (such as holding more low-carbon and sustainable assets to hedge against risks from high-carbon assets), among other practices.

We make the following recommendations to domestic financial institutions under the context of carbon neutrality:

Enhance the understanding of climate risks;

Conduct environmental climate stress testing and scenario analysis under the guidance of regulatory agencies;

Establish governance mechanisms and management frameworks for climate risks;

Improve pre-lending/pre-investing climate risk assessment, as well as post-lending/post-investing climate risk management

Strengthen environmental information disclosure capabilities;

Accelerate the development of carbon risk hedging tools.

5. Enhancing the Policy Framework for Green Finance to Achieve Carbon Neutrality

China’s green finance has developed rapidly in recent years. Regulatory authorities have been improving the top-level design of green finance, engaged in innovative practices, and achieved remarkable results in areas such as standard development, incentive mechanisms, product innovation, local trials, and international cooperation. China has become the first country globally to establish a systematic policy framework for green finance through top level design, and made considerable progress in the green finance market and product innovation. By the end of 2020, green loans held by major financial institutions in China reached nearly 12 trillion RMB, ranking first in the world, and outstanding green bonds amounted to around 1.2 trillion RMB, ranking second globally. Green finance assets prove to be good-quality, with the non-performing loan ratio of green loans far lower than that of total loans in commercial banks, and no default in green bonds.

In recent years, China has also initiated and participated in several important international initiatives on green finance. China and the UK jointly pushed for the discussion of green finance/sustainable finance in G20 for three consecutive years between 2018 and 2020, advancing international consensus on green finance development. In 2021, the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group was reestablished, with China once again serving as co-chair, to develop the G20 Sustainable Finance Roadmap. In December 2017, the PBC and Bank of France, together with six other central banks and regulatory agencies, jointly launched NGFS to conduct cooperative researches on the impact of climate risk on financial stability, environmental risk analysis, climate information disclosure, and the accessibility of green finance, achieving multiple consensus. Green Investment Principles (GIP) for the Belt and Road, jointly launched by the GFC and the City of London Corporation's Green Finance Initiative, have been widely recognized by the international community, with the endorsement of 40 global major institutions managing assets of $49 trillion.

However, China's existing green finance system faces several problems and challenges to achieve carbon neutrality.

First, the green finance standards are not fully aligned with the carbon neutrality goals. Although high-carbon projects related to fossil energy, such as clean coal technology, have been removed from the “Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue” (2021 edition), adjustments have not been made to other green finance standards (including green credit criteria and Green Industries Guidance Catalogue) , of which some projects don’t fully meet the net-zero carbon emissions requirements of carbon neutrality.

Second, the level of environmental information disclosure does not meet the requirements of carbon neutrality. Currently, most enterprises in China are not obligated to disclose carbon emissions and carbon footprints, and many financial institutions lack the capability to collect, calculate, and assess carbon emissions and footprints, resulting in insufficient disclosure of information related to brown/high-carbon assets.

Third, the incentive mechanisms for green finance need further improvement. Although financial regulatory authorities and local governments have provided incentive mechanisms, such as refinancing, interest subsidies, and guarantees for green projects, to mobilize private capitals to invest in green finance, the extent and coverage of incentives are still insufficient, particularly in incentivizing low-carbon and zero-carbon investments within green projects. Moreover, these incentive mechanisms have not yet incorporated carbon footprint as an evaluation criterion for investment or asset management.

Fourth, financial institutions need to enhance their understanding and analytical capability of transition risks. Some large institutions in China have conducted research on transition-related analysis models and methods, many financial institutions have not systematically carried out analysis of environmental/climate-related risks, and the risk management measures.

Fifth, green finance products cannot fully meet the requirements of carbon neutrality. China has made significant progress in green loans, green bonds, and other products. However, ESG products provided to investors still lack diversity and liquidity, and most green finance products are not yet linked to carbon footprints.

Last, due to the weak financial attributes of carbon, the carbon market has not fully played its role in guiding mid-to-long-term low-carbon investments.

To bridge the gap between China's existing green finance system and the carbon neutrality goals, it is recommended to further improve the policy frameworks for green finance from the perspectives of standards, disclosure, incentive mechanisms, and carbon market regulation. This will attract more social capital to participate in low-carbon and zero-carbon construction, and effectively prevent climate-related risks. The specific recommendations are as follows:

1). Revise the green finance standards based on the carbon neutrality constraint. Following the approach adopted by the “Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue” (2021 edition), it is suggested to remove high-carbon projects related to fossil energy, such as clean coals, from the statistical standards for green credit and the green industry catalogue, based on the requirements of carbon neutrality and the DNSH principle. The same principles should be followed when drafting the standards of green fund and green insurance.

2). Guide financial institutions to calculate and disclose the exposure to high-carbon assets and the carbon footprints of major assets. After defining the brown assets, regulatory authorities should require financial institutions to disclose environmental and climate information, including information on green and brown assets held by financial institutions and the carbon footprints of these assets. The disclosure requirements for carbon footprint-related environmental information should be gradually increased, aligned with the knowledge and capabilities of domestic institutions. Initially, financial institutions should disclose the risk exposure to brown or high-carbon industry assets they hold, as well as the carbon emissions and footprints of loan clients and investment targets. In the medium term, financial institutions should be further required to disclose the carbon footprints of major loans/investments and other financial products or assets.

3). Encourage financial institutions to conduct environmental and climate risk analysis and strengthen capacity building. Financial regulatory authorities and financial enterprises should conduct forward-looking environmental and climate risk analysis, including stress testing and scenario analysis. Industry associations, research institutions, and education and training organizations should organize experts to support capacity building and international exchanges for financial institutions. Financial regulatory authorities can lead macro analysis on climate related risks to assess their impact on financial stability, and consider requiring large and medium-sized financial institutions to gradually disclose the results of environmental and climate risk analysis.

4). Establish stronger incentive mechanisms for green finance to achieve carbon neutrality. In addition to the PBC’s commitment to introducing carbon emission reduction support tools, low-risk green assets can be included in the scope of qualified collateral for commercial banks to borrow from the central bank. Therefore, the risk weight of green assets can be reduced, and the risk weight of brown assets can be increased, while the overall risk weight of bank assets is maintained. Local governments with capabilities can increase support for local green projects through interest subsidies, guarantees, and other measures.